NEXT CHAPTER: ARTIST, CURATOR, AND EDUCATOR BENITO HUERTA RETIRES

ORIGINAL ARTICLE BY CASEY GREGORY | JULY 26, 2022 | ARTDALLAS/FT WORTH

There’s a reason why most artistic movements are named after they have ended. It’s not necessary to see the forest for the trees when you’re busy watching your feet to avoid the fallen logs along your path. So, it’s rare that an artist is able to conceive of the arc of their own work as a project of decades as they are in the midst of the project. Benito Huerta is this kind of artist. “I kind of go in and out in technique,” he says.

What is consistent is Huerta’s focus on the social and political realities of our lives, butted up against the elegance of our constructed collective narrative. “Some things have not changed,” Huerta says. He recalls a painting he made in 1976: “One of the things I did at U of H was taking images out of the newspaper, showing street fights and people in emotional turmoil. I did a painting…before I went to graduate school of a Black kid lying on the street. I thought it was really strong.” In Ferguson when Michael Brown was killed, he felt a sense of déjà vu. “The subject matter was relevant then and relevant now.”

Or continue reading below.

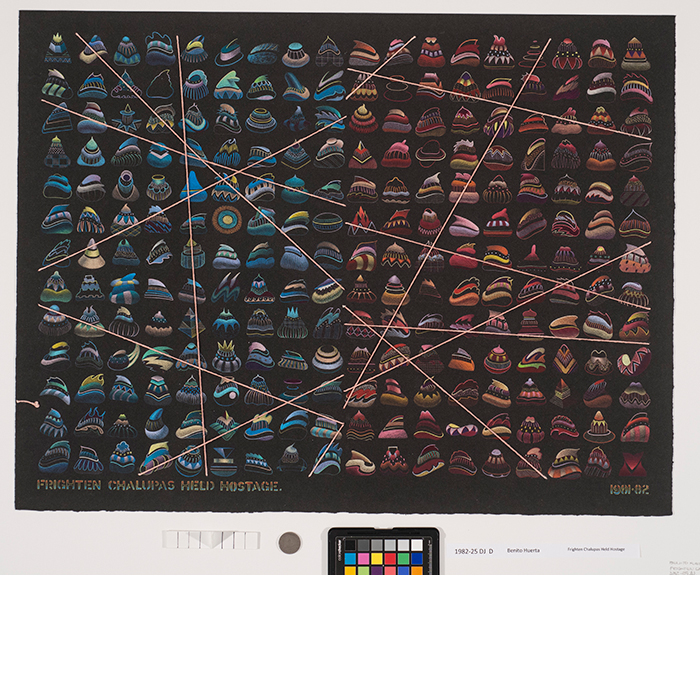

Frighten Chalupas Held Hostage, 1982

Color pencil, string on black Arches paper

20 ½” x 29”

Collection of the Menil Collection, Houston, Texas

The artist has held roles as Professor and Curator at the University of Texas at Arlington for twenty-five years, and the occasion of our conversation is his retirement. As Huerta walks away from the academic position, he is also mounting twin retrospectives in two locations, affording his home base of Arlington a kind of gravitational pull. This is fitting, since Huerta’s curatorial role has kept the University gallery punching above its weight for many years in a town more associated with sports teams than visual culture. Fort Worth’s William Campbell Gallery will feature Huerta’s work in More or Less, which he describes as containing the more “adult” pieces of his oeuvre, beginning Nov. 5 and running through Jan. 7. The Latino Cultural Center presents Mas o Menos Nov. 11 though Jan. 7.

A major series of works in the Campbell exhibition features moments of mass violence as viewed from a distance. “An image that I’ve been dealing with is the mushroom cloud,” Huerta says. This nuclear form is overlaid with the word INTERMEZZO, which is a moment of respite in an opera. Living as we do in an era of peak image saturation, Huerta’s text paintings are weirdly familiar. They perform the same function as memes, but their scale and the skill with which they executed gives them a weight that isn’t achievable on a backlit screen. In the way that Renaissance and Baroque era classical painters focused on iconic moments of violence as a symbol—the compromised body of Christ or a saint—Huerta unveils our contemporary icons of suffering. “I was brought up Catholic, but I don’t practice religion,” he says. “I believe in God, but I don’t know what God is because he’s never told me.”

While refraining from the direct moralizing found in religious imagery, his works do contain something of a holy ghost. The haunting we are subjected to takes the form of questions: about what we as a society have wrought and where we are headed. As part of the same triptych series, Huerta superimposes the word INTERMISSION over a view of the Twin Towers burbling smoke into a clear sky. “As you take a break in a long movie it gives you time to contemplate what has happened,” he explains, “and what will happen next.” Huerta suggests that 9/11 represented a terrible kind of innovation. “Nobody has used a plane as a missile. Human beings could actually think of those kinds of things,” he muses.

In the face of such ghastly creativity, Huerta sees that artists can provide some answers to the question of “what might happen next.” He explains, “I was reading an article about how some people in the department of defense went to Hollywood {after 9/11},” because they needed help narratively projecting from such an unprecedented moment. Storytellers were capable of projecting what was “born out of a situation or a moment in time.” Vision is what is gained by that kind of artistic “distance,” but it’s a careful balancing act because when dealing with such dire issues, one must not lose sight of the human frame of reference.

He gives the example of a graduate school painting, after Velazquez. “I was being reverent to the image,” he explains. He laughs recalling how when abstract expressionist Norman Bluhm saw the piece he said, “you need to do more splatters!” Huerta thinks about this in relation to his own career as a professor. “I have to remind myself to always be aware when I’m critiquing, what is it that they’re trying to get across? I try to do that,” he says. “I think that’s what professors should be doing.”

In many ways, Huerta’s tripartite career has been a method for excising small talk. His intentionality across his artistic career and his academic one are rooted in his own formative artistic experiences. “You would talk about each other’s ideas. You weren’t pulling punches because you were all learning. But once you get out of graduate school everybody becomes their own little corporate entity,” he laughs. The subjects he’s chosen to engage across the decades—the history of art, language, patriarchy, colonialism and empire, the role and limitations of artists—have led to a breadth of images that evidence our own uniquely American patterns. As the artist puts it, “in painting, sometimes you come back to the same subject again. It frees you up.”

—CASEY GREGORY